This blog will now be on a weekly posting schedule. This will allow me to improve the quality, depth of research, and length of my postings. All postings will be submitted on Saturday or Sunday each week.

In the next couple of weeks, I am going to post two movie reviews: one of Schindler’s List, and the other of The Dark Knight. Please stay tuned for the one on Schindler’s List: it will be good, and hopefully it will be next week. If not, there will be an analysis of the Dark Knight, and Schindler’s List will come the week after.

The following post is a copy of a paper that I wrote when I was 20. Because this paper was crucial to the development of my understanding of psychiatry, I am leaving it here to pave the way to a more advanced and sophisticated understanding reflected in future posts. After the paper, there is a short afternote, where I briefly summarize my current position on the paper. Although the paper is itself crystal clear (assuming a grasp of the technical vocabulary), my current position as reflected in my afternote will not be completely comprehensible until I write several more posts.

Schizophrenia’s Evolution as Shamanism

Introduction

Recent evolutionary theorists on the origin of schizophrenia have posited that the relatively high incidence of schizophrenia, combined with the low fecundity rate of schizophrenics and high heritability of schizophrenia, cannot be explained by any other means but by genetic selection for schizophrenia (Crow, 1995). Theories by Polimeni, et al. (2002), have suggested a link between group selection for the schizophrenic genotype and shamanism, believing the perpetuation of shamanism to be related to group advantage but also to the advent of schizophrenia in modern societies. Indeed, Polimeni, et al. have shown that if the size of hunter gatherer groups was 120-160, and with schizophrenia reaching incidences of 1% today, then every hunter-gatherer group would likely have a shaman.

This paper examines the hypothesis that schizophrenia is an evolutionary result of selection for shamanism. Since the vast majority of evolution occurs within the context of hunter-gatherer society, the validity of this hypothesis must be ascertained through the examination of hunter-gatherer societies. Several arguments underlie this broader hypothesis and elucidate the evolution of shamanism:

First, shamanism shares many behavioral parallels with schizophrenia; second, shamanism epitomizes the religious experience and provides critical religious guidance in hunter-gatherer societies; third, religion is an evolutionary adaptation necessary to deal with anxiety; fourth, shamanism, as a specialization in receiving religious experience, is also characterized by functional neurobiological alterations with an identical genetic basis to schizophrenia but a distinct and disparate etiology; last, the etiology of schizophrenia mirrors that of the etiology of religion, primarily derived from anxiety, stress, and loss of control.

What is schizophrenia?

First extensively studied and classified into mental disorder dementia praecox by German psychologist Emil Kraepelin (1896) and later re-termed schizophrenia by Eugen Blueler (1911), schizophrenia is characterized by an extended duration of two (or more) symptoms including “social withdrawal, depersonalization (intense anxiety and a feeling of being unreal), loss of appetite, loss of hygiene, delusions, hallucinations (e.g., hearing things not actually present), and/or the sense of being controlled by outside forces” (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). These symptoms must be precipitated by “social or occupational dysfunction” and not be the result of a general medical condition or the use of psychotropic drugs (American Psychiatric Association, 1994).

What is shamanism?

Shamanism exists worldwide almost universally among hunter-gatherer groups (Eliade, 1974). Ethnologists have historically interchangeably utilized the terms “shaman,” “medicine man,” “sorcerer,” and “magician.” Shamanism, while incorporating a vast number of practices, including magic, medicine, poetry, storytelling, and mysticism, cannot be defined in terms of these practices alone (Eliade, 1974). Instead, shamanism must be defined in terms of what its core function for the community is, and that is the specialist of religious experience (Eliade, 1974) and purveyor to the broader community the information gleaned from this exclusive experience (Krippner, 2000).

Varying sorts of religious experience are involved in shamanic trance. Three major varieties are visions, soul flight, and transformation into animal spirits. Soul flight, according to Eliade, is a form of “trance during which [the shaman’s] soul is believed to leave his body and ascend to the sky or descend to the underworld” (pg. 5). The means by which this journey occurs depends largely upon the cultural context. Khant shamans walked up a branch lowered from the sky; Ninets, a bridge made of smoke; the Chukchi would ride on a reindeer (Vitebsky, 2001).

Visions consisted of seeing spirits or seeing the souls of observers. The shamans would often consult with spirits, to plead with them to return to a sick body or to ensure good weather. Occasionally, the shamans would battle with malevolent spirits or enlist the aid of beneficial ones (Vitebsky, 2001).

Adolescent pre-shamans often become meditative, seek solitude, sleep a great deal, seem absent-minded, and have prophetic dreams and sometimes seizures (Czaplicka, 1914). These pre-shamanic behaviors are reminiscent of minor schizophrenic behaviors. And as with schizophrenia, the activation of shamanism (i.e. “a call from the gods”) is precipitated by stress and anxiety. Additionally, the capacity for this activation is often hereditary for shamanism (Eliade, pg. 15).

The becoming of a shaman; how a shaman guides society

Shamanistic initiatory practices, like shamanism itself, vary in traditions from culture to culture. In a great many cultures, a call from the gods is necessary, which at a young age, among the Siberian Vogul, may consist of a number of “exceptional traits,” such as nervousness and sometimes epileptic seizures (Eliade, pg 15). Oftentimes the call from the gods is marked with a certain degree of derangement (pg 17).

Following the recognition of the pre-shaman as “called upon by the gods” due to idiosyncratic behaviors and experiences, the pre-shaman undergoes an extensive initiatory tutelage, in which he learns two important aspects of shamanism: the extensive folklore and rituals of the group and the capacity to invoke ecstasy, which is the vessel of religious experience. As a result of this training, the shaman is prepared to provide a number of functions for their society, such as medicine, religious guidance, and the perpetuation of a group’s myths. Without shamanism, a society would be left without a compass for religious activity.

But why is religious activity so important? What advantage does religiosity confer to a hunter-gatherer group? To answer this question, the motive behind the formation of religion must be ascertained.

Origins of religion

In order to understand the function of the shaman within a broader religious context, we must understand the psychological origin of religion and what this origin entails about the shamanic experience. Throughout history, the broad general consensus regarding the psychological origins of religion entails that religion is spurned from the fears and needs of man in the face of an unpredictable world.

David Hume writes in 1757:

[U]nknown causes…become the constant object of our hope and fear; and while the passions are kept in perpetual alarm by an anxious expectation of the events, the imagination is equally employed in forming ideas of those powers, on which we have so entire a dependence…though [man’s] imagination, perpetually employed on the same subject, [they] must labour to form some particular and distinct idea of [unknown causes]. The more they consider these causes themselves, and the uncertainty of their operation, the less satisfaction do they meet with in their researches; and, however unwilling, they must at last have abandoned so arduous an attempt, were it not for a propensity in human nature, which leads into a system, that gives them some satisfaction.”

In 1891, anthropologist R.H. Codrington stated in his anthropological study in Australia:

The Melanesian mind is entirely possessed by the belief in a supernatural power or influence, called almost universally mana. This is what works to effect [sic] everything which is beyond the ordinary power of men, outside the common processes of nature; it is present in the atmosphere of life, attaches itself to persons and to things, and is manifested by results which can only be ascribed to its operation.

Several other theorists posit similar explanations (Frederick, 1919; Buck, 1939).

These theorists all centrally establish fear and uncertainty in the face of the unpredictable, dynamic power of nature. Indeed, Freud (1913) asserts that the totemization (read: deification) of animals, plants, or other natural forces coincides with the peculiar power relation that this object has with the group. This power relation always relates abstractly to the unpredictability of nature and what we desire from the element of nature that this totemization/deification represents. The types of objects totemized/deified include the sky, animals, volcanoes, rain, the moon, and the sun, (Freud, 1913) all objects that have a critical influence on the livelihood of the group (excepting some other kinds of deified creatures, such as birds, but even in this case, the bird’s wisdom is often consulted to deal with the rigors placed upon a people by other forces). P.H. Buck (1939) elaborates in his study of the Polynesians:

In this early form of supernatural government by the gods, special departments were created for the major gods. The major gods became departmental gods and were appealed to according to the particular desires of the people. Takne was given Forestry and hence controlled trees, birds, and insect life. He naturally became the tutelary deity of wood craftsmen. Before a tree could be felled in the forest for a voyaging ship or an important house, Tane had to be placated with a ritual chant or invocation; and before commencing an important task, an offering was made to Tane by the craftsmen…Rongo presided over Horticulture and Food and, as a plentiful supply can be produced by cultivation only in a time of peace, Rongo became the God of Peace. Tangaroa ruled over the Marine Department and hence was appealed to by deep-sea voyagers and fishermen.

The hunter-gatherer, or at least the pre-agriculturalist, as in Buck’s account, deifies the unpredictable, natural force in order to transform it into an entity with whom the hunter-gatherer can communicate. This deified natural force, then, is bartered with to confer gifts to the hunter-gatherer. When the hunter-gatherer supplicates to this deity, it provides him with a form of anxiety relief, insofar as he believes he is doing something productive to alleviate his stressful situation. The deification, then, serves as a construct through which to habitually relieve anxiety when unpredictable situations in the natural world present themselves.

Appeal to deities, then, corresponds to the extent to which a primitive people need the services the deities control for livelihood. What must happen if the deities do not oblige? What if the dynamic power of nature is not forgiving? This is the very thing the perpetuators of religion fear, for if the gods do not accept their prostrating, then it will be their death. If the deified sky doesn’t give rain, if the deified tree does not bear fruit, if the volcano explodes in spite of the hunter-gatherers’ sacrifices they make at his feet, they face the prospect of potential imminent mortality. The origin of religion, then, can be seen as an attempt for the hunter-gatherer to acquire some kind of control over his own mortality in the face of an unpredictable, natural world.

Terror Management Theory

This explanation of the origin of religion posits that fear and uncertainty as a result of chaotic natural processes prelude the conceptualization of an abstracted higher power that symbolizes these processes. This is precisely what is predicted by what is known as Terror Management Theory, which states that the evolution and acceptance of a shared cultural world view has provided a means by which humans cope with the existential anxiety created by death awareness:

TMT starts with the proposition that the juxtaposition of a biologically rooted desire for life with the awareness of the inevitability of death (which resulted from the evolution of sophisticated cognitive abilities unique to humankind) gives rise to the potential for paralyzing terror. Our species “solved” the problem posed by the prospect of existential terror by using the same sophisticated cognitive capacities that gave rise to the awareness of death to create cultural worldviews: humanly constructed shared symbolic conceptions of reality that give meaning, order, and permanence to existence; provide a set of standards for what is valuable; and promise some form of either literal or symbolic immortality to those who believe in the cultural worldview and live up to its standards of value. Literal immortality is bestowed by the explicitly religious aspects of cultural worldviews that directly address the problem of death and promise heaven, reincarnation, or other forms of afterlife to the faithful who live by the standards and teachings of the culture. Symbolic immortality is conferred by cultural institutions that enable people to feel part of something larger, more significant, and more eternal than their own individual lives through connections and contributions to their families, nations, professions, and ideologies (Solomon, et al., In Press).

This theory predicts that when the salience of mortality awareness is increased in an individual, such as in the situation of resource scarcity, then the individual responds by reinforcing his worldview. In the case of a hunter-gatherer, this might mean a reaffirming of religious beliefs and a corresponding increase in religious ceremony and appeal to the gods. In the context of a modern society, this reinforcement of worldview is verified by empirical studies (Solomon, et al., 1997).

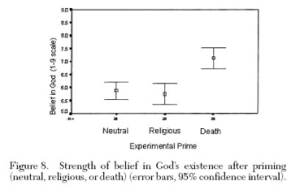

One such study, by Altran and Norenzayan (2004), exposed subjects to different stories. Each story began the same, a narrative of a day of the life of a boy. Each progressed in different directions, one of a religious nature, one that intimately discussed the death of a person, and one that was neutral and mundane. Following each story, subjects were asked to divulge the extent of their belief in God through a questionnaire.

The results clearly show that when exposed to the story about a death, the subjects had a significantly strengthened belief in God. In a separate study, the same thing story scenario was played out, but then, the subjects were given a questionnaire regarding their strength of belief in supernatural power of prayer.

Again, the same sorts of results were gleaned. Each study provides substantial evidence for the reality of Terror Management Theory.

Terror Management Theory, therefore, holds as a scientifically validated theory: religion is characterized fundamentally as a reaction to anxieties related to death in an uncertain world. If shamanism is considered the epitome of religious experience in a hunter-gatherer society, shamanism must be inextricably related to these gross mortality anxieties facing the hunter-gathering man in an uncertain world. Indeed, a large part of the shamanic initiation rituals involves the hallucination of dismemberment, death, and rebirth.

If schizophrenia parallels shamanism, then the etiology of schizophrenia should also be characterized by stress and anxiety. In order to determine this, the etiology of schizophrenia must be elucidated.

Etiology of schizophrenia

There is widespread consensus that there is a genetic component of schizophrenia, with estimates of heritability around 80% (Owen, et al., 2003). These estimates correspond well with psychiatric practicioners’ and researchers’ knowledge, and they suggest a significant environmental influence on the genesis of schizophrenia (Rapaport, 2005). Additionally, this degree of heritability is not contrary to observed ethnographic accounts of shamanistic heritability. The model describing the interaction between this genetic component and the environmental influence in the etiology of schizophrenia is called the neurodevelopmental model.

The neurodevelopmental model, while recognizing the disorder’s vast heterogeneity (Sperner-Unterweger, 2005), postulates psychosis-predisposing neurophysiological alterations in early neurodevelopment (Murray and Lewis, 1987; Bullmore et al., 1998; McDonald et al., 1999) and activation of the psychotic condition through stressful events in late adolescence or early adulthood (Broome et al., 2005). This neurodevelopmental model, in other words, proposes structural and/or biochemical changes in development, which predispose the individual to aberrant brain activity (psychosis) later in life.

A large body of studies of prenatal complications during neurodevelopment abound. Rates of schizophrenia have been shown to be increased significantly among individuals exposed to prenatal famine (Susser and Lin, 1992). Moderate to severe illnesses and infections, death of spouse, and experience of catastrophic events during prenatal periods have been shown to increase risk of schizophrenia in the cohorts studied (Cannon, 2005). Indeed, in animal models, even mildly elevated maternal stress levels during prenatal development have shown to increase vulnerability to adverse life events (Hougaard, 2005).

Neurodevelopmentally, childhood is a critical moment and aberrant mental states at this time have shown to increase the risk of later development of schizophrenia. It has been demonstrated that children that later develop schizophrenia are more likely than peers to show subtle developmental delays and cognitive impairments, as well as having the tendency to be solitary and socially anxious (Cannon et al., 2002). Depression is both one of the first exhibited symptoms in most pre-schizophrenic individuals and is an extremely common comorbidity (a psychopathology that exists along with schizophrenia) (Cannon, 2005). While up to 25% of all individuals in one study have been found to experience a psychotic symptom by age 26 (Poulton, et al., 2000), only 1% of all individuals actually progresses from this “prodromal” (pre-schizophrenic) symptomology to frank schizophrenia. Indeed, depression has been theorized as a major factor in this transition (Escher, et al., 2002).

In adulthood, prolonged stress or depression in a predisposed individual can lead to a schizophrenic episode in neurophysiologically predisposed individuals (Murray and Lewis, 1987; Bullmore et al., 1998; McDonald et al., 1999; Cannon, 2005). An interview with Robert Strong, MSW, a social worker from California yielded the observation that the majority of schizophrenics, directly prior to their psychosis, experienced either a chain of stressful events or one particularly traumatizing event. He also indicated a pattern of childhood traumatic experiences, such as physical abuse.

The neurobiology of schizophrenia is extensively studied but not well understood. The reduction in volume of various brain structures has been documented, as well as an increase in ventricular volume–the spaces within the brain between various brain structures, present in all individuals (McDonald et al., 1999; Wright et al., 2000). The pituitary gland, a major component of endocrine function in the body, has been shown to be enlarged in first-episode schizophrenics, which has been explained to be indicative of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA) hyperactivation, which is the biochemical parallel of the stress response. Higher blood cortisol concentrations are also demonstrated (Pariante, 2004a). These neuroendocrinological markers are also present in depressed patients and shown to exist in a host of other stress conditions (Pariante, 2004b), which reinforces the stress-induced psychosis hypothesis.

Ventricular spaces in schizophrenics are enlarged and the brain has been shown to be several percentage points smaller (Wright et al., 2000). Excessive apoptosis (programmed cell death) and synaptic pruning (the loss of connections between neurons) during adolescence is postulated as an explanation, each of which normally happen but which happen in excess in schizophrenia (Jarskog et al., 2005). Both the amygdala and the hippocampus, which together are responsible for maintaining the individual in emotional balance, are found to be reduced in volume by a mean of 5% in schizophrenic patients (Wright et al., 2000). These two structures play a large role in regulating salience of incoming information. In other words, they are responsible for determining what we pay attention to. Dysfunction in these two limbic structures, or lack of regulation by the prefrontal cortex, can result in the dysregulation of dopamine, the principal neurotransmitter governing attention processes. This dysregulation can cause emotional disturbances and information overload due to increased salience to innocuous information, leading to psychosis (Grace, 2004). McGhie and Chapman (1961) quote a patient as stating, “My thoughts get all jumbled up…Things are coming in too fast. I lose my grip and get lost. I am attending to everything at once and as a result I do not attend to anything.”

Differing phenomenon, differing etiologies

Indeed, then, stress does play a critical role in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia, as would be predicted by the hypothesis of its genetic equivalence to shamanism. Important, as well, are the religious and morbid ideations of schizophrenia. According to my friend Robert Strong, MSW, a social worker in California, the vast majority of schizophrenics focus on atypical and intense religious experience. What, then, differentiates the psychotic from the socially adjusted, albeit occasionally eccentric, shaman?

I argue that the divergence in etiology is grounded on differing socio-cultural environments. The shaman’s unstigmatizing, encouraging, and accommodating to his pre-shamanic hysteria. The schizophrenic’s is harsh, condemning, and alienating to his perceived psychopathology. This disparity in etiology between schizophrenia and shamanism is what, in the case of schizophrenia, results in thought disorder, hallucinations, delusions and crippled socio-functionality, and what in the case of shamanism, results in the seeking of solitude, an occasionally nervous disposition, and the attunement to religious experience. This is borne out by both psychoanalytic and neurobiological evidence.

Julian Silverman’s (1967) psychoanalytic approach perceives schizophrenia and shamanism as internal conflict resolution processes and outcomes that are either condoned or rejected by a given culture. If condoned, these irresolvable conflicts are consolidated in the person’s psyche, and the new state of shamanism adheres to the expectations of culture while simultaneously serving as an escape mechanism to an acute and irresolvable conflict. If rejected, contemporary culture denies the legitimacy of this process of escape, and so not only does the schizophrenic have the burden of an illegitimate thought process, but the schizophrenic is burdened by the anxiety resulting from a condemnation of self. This, according to Silverman, aggravates the problem facing schizophrenics and significantly reduces their potential for a positive prognosis. Ackerknecht (1943) anticipates Silverman’s psychoanalytic theory by asserting that “in primitive societies there perhaps exist outlets for mental conditions with which we are not able to deal. It seems as if we will have to accept the fact that shamanism is not a disease but being healed from disease.”

Reinforcing Silverman’s interpretation is neurobiological data. In an interesting animal analogy, a primate’s standing in the social hierarchy can influence occupancy at dopamine receptors. Individually housed and socially subordinate macaque monkeys have high levels of synaptic dopamine, whereas those who are able to attain dominance in social housing are able to return to ‘normal’ dopamine levels. Hence, living alone or being in a lower position in the social hierarchy may be, at least for macaque monkeys, associated with a hyperdopaminergic state (Morgan, 2002). Clearly, this illustrates that the social condemnation of pre-shamanic behaviors could potentially exacerbate and transform these relatively benign characteristics into a full blown pathology.

Additionally, while a shaman can somewhat attenuate his initially aberrant mental state and high stress levels through the mastery of shamanic practices, the modern day schizophrenic has no such outlet. Due to social stigma and isolation, the schizophrenic’s stress and anxiety is amplified, leading to hypercortisolism and depression (Steptoe, et al., 2004), two crucial components in the etiology of schizophrenia.

Conclusions

To summarize, I argue that stress and anxiety are critical not only to understanding the religious experience of a shaman but to understanding religion in general, with shamanism being but an expression of broader religion. Furthermore, I argue that the stress-mediated activation of the schizophrenic condition is a functional adaptation of hunter-gatherer societies and their necessary religious practices. In hunter-gatherer societies, this stress reflects a reminder of potential imminent mortality and serves to foment both the construction and reinforcement of religious belief. This is predicted by Terror Management Theory and experimental studies have shown that the salience of mortality awareness significant correlates with the reinforcement of worldview. The extent to which the threat of imminent mortality governs the lives of individual hunter-gatherers determines the reinforcement of religious worldview.

Therefore, I argue, this reinforcement of religious worldview also corresponds with increased insistency of religious ceremony as a means of catharsis and appeasement toward deified natural forces. The degree of this insistence of religious ceremony determines the extent to which intense shamanic experience is necessary. Consequently, the presence of stress as a result of hunter-gatherer uncertainty in subsistence is the direct cause of the selection for shamanism.

Particularly striking is the strong correlation between pre-natal famine and schizophrenia (Susser and Lin, 1992). Is shamanic activation related to the routine exposure to famine? This, again, is predicted by the model that shamans serve as communicators and appeasers of the gods and therefore the stressful situation imposed by potential imminent mortality.

Additionally, the religious experience itself is fundamentally distinct from any other sort of human cognitive function necessary for survival. Hereditary, distinct, prevalent across cultures, highly functional in the context of hunter-gatherer societies, and behaviorally parallel to schizophrenia, shamanism has a genetic basis, and the persistence of its modern analogue, schizophrenia, can be explained on this basis. Modern stress, a mime to the threat of imminent mortality (social stress is the predominant modern stress form), triggers the shaman genotype, but the development spirals out of control as the individual can find few outlets for shamanistic expression. This, in turn, perpetuates schizophrenia. The schizophrenic individual is pathologized, stigmatized, and thrown into insane asylums, a kind of man for which society no longer has a wholesome accommodating function.

Works Cited

Ackerknecht, Erwin, H., 1943. Psychopathology, Primitive Medicine and Primitive Culture. Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 14, 30-67.

Aggarwal, Y., Williams, M.D., Beath, S.V., 1998. Neonatal origins of schizophrenia. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 78:1-8.

American Psychiatric Association, 1994. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th edn) (DSM–IV). Washington, DC: APA.

Codrington, R.H., 1891. The Melanesians. HRAF Press. New Haven.

Bleuler, E., 1911. Dementia praecox oder Gruppe der Schizophrenien. In: G. Aschaffenburg, Editor, Handbuch der Psychiatrie, Deuticke, Leipzig, pp. 1–420.

Broome, M.R., Wooley, J.B., Tabraham, P., Johns, L.C., Bramon, E., Murray, G.K., Pariante, C., McGuire, P.K., Murray, R.M., 2005. What causes the onset of psychosis? Schizophrenia Research, 79, 23-24.

Bullmore, E.T., Woodruff, P.W., Wright, I.C., Rabe-Hesketh, S., Howard, R.J., Shuriquie, N., Murray, R.M., 1998. Does dysplasia cause anatomical dysconnectivity in schizophrenia? Schizophrenia Research 30, 127-135.

Cannon, M., Clarke, M.C., 2005. Risk for schizophrenia – broadening the concepts, pushing back the boundaries. Schizophrenia Research 79 5-13.

Cannon, M., Jones, P.B., and Murray, R.M., 2002. Obstetric complications and schizophrenia: historical and meta-analytic review, Am. J. Psychiatry 159, pp. 1080–1092.

Crow, T.J., 1995. A Darwinian approach to the origins of psychosis. Br J Psychiatry 1995; 167: 12-25.

Czaplicka, M.A., 1914. Aboriginal Siberia: a Study in Social Anthropology. Oxford.

Eliade, M., 1974. Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy. Princeton University Press.

Freud, S., 1913. Totem and Taboo; resemblances between the psychic lives of savages and neurotics. W. W. Norton & Company. New York.

Grace, A., 2004. Developmental dysregulation of the dopamine system and the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. In: Keshavan, M.S., Kennedy, J., Murray, R. (Eds.), Neurodevelopment and Schizophrenia. Cambridge, Cambridge.

Harrison, P.J., Owen, M.J., 2003. Genes for schizophrenia? Recent findings and their pathophysiological implications. The Lancet, 361, 417-419.

Holden, C., 2005. Cracking open psychosis. Science Now.

Hougaard, K.S., Andersen, M.B., Kjaer, S.L., Hansen, A.M., Werge, T., Lund, S.P., 2005. Prenatal stress may increase vulnerability to life events: Comparison with the effects of prenatal dexamethasone. Developmental Brain Research Vol. 195, 55-63.

Jablensky, A., 1995, Schizophrenia: recent epidemiologic issues, Epidemiol. Rev. 17 (1), pp. 10–20.

Jarskog, L.F., Glantz, L.A., Gilmore, J.H., Lieberman, J.A., 2005. Apoptotic mechanisms in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. Progress in neuro-psychopharmacology & biological psychiatry. 29(5), 846-58.

Kraepelin, E., 1896, Lehrbuch der Psychiatrie (5th ed.), Barth, Leipzig.

Krippner, S. 2000. The epistemology and technologies of shamanic states of consciousness. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 7, 93-118.

McDonald, C., Fearon, P., Murray, R., 1999. Neurodevelopmental Hypothesis of Schizophrenia 12 years on: Data and Doubts. In: Rapoport, J. (Ed.), Childhood Onset of “Adult” Psychopathology, American Psychiatric Press, Washington, pp. 193-220.

McGhie, A., Chapman, J., 1961. Disorders of attention and perception of early schizophrenia. Br. J. Med., 103-116.

Murray, R.M., Lewis, S.W., 1987. Is schizophrenia a neurodevelopmental disorder? British Medical Journal, 295, 681-682.

Owen, M.J., O’Donovan, M. and Gottesman, I.I., 2003. Psychiatric genetics and genomics, Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 247–266.

Pariante, Carmine M., Jul. 2004. Pituitary volume in psychosis. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 185, 5-10.

Pariante, Carmine M., Nov. 2004. Pituitary volume in psychosis: Author’s reply. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 185(5), 437-438.

Polimeni, J., Reiss, J.P., 2002. How shamanism and group selection may reveal the origins of schizophrenia. Medical Hypotheses 58(3), 244-248.

Rössler, W., Salize, H.J., Os, J.v., Riecher-Rössler, A., Size of burden of schizophrenia and psychotic disorders. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 15(4), 399-409.

Solomon, S., Simon, L., Greenberg, J., Harmon-Jones, E., Pyszczynski, T., Arndt, J., Abend, T., 1997. Terror Management and Cognitive-Experiential Self-Theory: Evidence That Terror Management Occurs in the Experiential System. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 72, 1132-1146.

Starr, F., 1919. The origin of religion. John Higgins Printer. Chicago.

Susser, E., Lin, S.P., 1992. Schizophrenia after prenatal exposure to the Dutch Hunger Winter of 1944-1945. Archives of General Psychiatry 49, 983-988.

Wright, I.C., Rabe-Hasketh, S., Woodruff, P.W.R., David, A.S., Murray, R.M., Bullmore, E.T., 2000. Meta-Analysis of Regional Brain Volumes in Schizophrenia. American Psychiatric Association, 157:16-25.

Sperner-Unterweger, B., 2005. Biological hypotheses of schizophrenia: possible influences of immunology and endocrinology. Fortschritte der Neurologie-Psychiatrie, 73 (Suppl 1), 38-43. Susser, E., Lin, S.P., 1992. Schizophrenia after prenatal exposure to the Dutch Hunger Winter of 1944-1945. Archives of General Psychiatry 49, 983-988.

Vitebsky, P., 2001. Shamanism. University of Oklahoma Press. Norman, Oklahoma.

Afternote

While this paper raises several crucial problems, these can only be said to produce further knowledge by reframing and transcending them. The problems addressed in this paper are central to the theoretical orientation of psychiatry in the 1960s–which I claim has not changed to the present day but rather only brought from latency to full fruition, to a large degree in 1980–and the orientation of late 20th century/early 21st century evolutionary theory. Since the theoretical orientation discussed here comes from 1960s psychiatry–and this theoretical orientation not been advanced upon in spite of crucial difficulties in contemporary psychiatric theory–the theoretical orientation of this paper is inadequate: it is an incomplete perspective of psychiatry. Future posts will seek to establish the claim that psychiatry has not changed its theoretical orientation in the 1960s, to establish what precisely that orientation is, and in doing so, overcome or at least make clear the reasons for some of its problems.

“I guess I’ve been waiting so long I’m looking for perfection. That makes it tough.”

“I guess I’ve been waiting so long I’m looking for perfection. That makes it tough.”